“Smart contracts aren’t legal contracts,” they say.

They’re right. But that’s missing the point.

Smart contracts were never intended to be legal contracts. Nick Szabo wanted to create new digital institutions: agreements enforced in code, rather than courts. It was obvious that physical courts (paper-driven, inefficient intermediaries that they are) could not keep pace with the Internet. A rapid influx of cross-jurisdictional transactions would further overwhelm a system already struggling to provide access to many. Even Satoshi expressed interest in supporting a wide range of commitments in the Bitcoin script. Today, smart contract platforms like Tezos continue Szabo’s work and allow us to make commitments with strangers on the Internet — in code.

Why do we need contracts?

In a world without contracts or currency, we’re limited to simultaneous barter — you have an apple, I have a loaf of bread, and we trade on the spot. However, the more we trade, the more likely we’ll run into an issue which economists call the double coincidence of wants: in order for us to trade, I must want the apple at the same time that you want bread. That’s not very likely.

Money is one solution to this problem. I can sell the loaf of bread, and later exchange the money for an apple or another item. With money, we can reduce the number of ‘wants’ from two to one — I don’t have to need the items that you have to trade; I can still get an apple later. The temporal requirement has been lifted.

Contracts work similarly, but they facilitate even more potential transactions. There’s no simultaneous exchange of value required, not even of money. I can sell a loaf of bread now, and someone can promise to pay me back next month. Such a capability radically expands the types of transactions we can make.

But there’s still a problem. How do you know that I’ll keep my promise to repay you? How do we create credible commitments?

Enforcing Promises

Early modern thinker Thomas Hobbes recognized the problem of enforcing promises:

“bonds of words are too weak to bridle men’s ambition, avarice, anger, and other passions, without the fear of some coercive power” (Leviathan, p. 69).

He argued, furthermore, that the enforcement of contracts was one of the primary functions of government. That is to say, we only keep our promises to one another under the threat of force. Yale Law School professor and former dean Anthony Kronman points out that the state can be thought of as an enforcement machine. He also argues that, were the machine privately owned, contracting parties would pay for its use.

Taking the idea of an enforcement machine almost literally, in the mid-90s Nick Szabo invented the idea of a smart contract — a contract that would be run on secure hardware and would enforce itself without needing to rely on a court.

Smart contracts, or just blockchain code?

However, around 2013, the cryptocurrency world expanded the concept of smart contracts. The Ethereum white paper, for example, uses “contract” as an all-purpose term to mean code that runs on a blockchain.

This new definition shifted the focus of smart contracts. Instead of simply enforcing commitments, the purpose of these “contracts” is unclear. The new definition also obscured a rich history of smart contracts: following Szabo’s work in the 1990s, Mark Miller of Agoric wrote in 2003 about split contracts (smart contracts made of two or more parts, some automatically enforced in code and others — such as instructions for arbitration — which are not). There were even smart contract platforms prior to the Internet, such as AMIX, the American Information Exchange, the “world’s first online market for information and expertise.” Built in the 80s and 90s, AMIX was extraordinary for its time, allowing users to securely sell their experience as consultants.

Satoshi Nakamoto thought that commitments would be a key aspect of Bitcoin’s future. “The design supports a tremendous variety of possible transaction types that I designed years ago,” Satoshi said in 2010. “Escrow transactions, bonded contracts, third party arbitration, multi-party signature, etc. If Bitcoin catches on in a big way,” she or he explained, “these are things we’ll want to explore in the future.”

Tezos creates a platform for smart contracts in the original sense: not as code for a world computer, but as a way to enable transactions. At the same time, Tezos’ blockchain language, Michelson, is Turing complete and formally specified, and can support a wide variety of different use cases.

Can “Smart Contracts” Replace Contracts?

Can smart contracts really replace some of the uses of legal contracts? The answer is yes, but the uses are currently limited.

Let’s say that I want to sell an item online — but, instead of going on Ebay, I want to use a peer-to-peer marketplace. Selling items to strangers online, possibly across legal jurisdictions, creates exactly the kind of transactional insecurity that concerned Hobbes. In our exchange, whoever goes first risks having the other party break their promise. If I send the item first, they might not pay for it; if they pay for it, I might not send it.

The solution is a multisig smart contract, such as this example (courtesy of Milo Davis) or this higher level example written in Liquidity (courtesy of OCamlPro). In a multisig contract for online transactions, two of three signatures (the buyer, seller, and a neutral third party) can be required. The third party could be anyone (or anything that we trust to resolve disputes in an unbiased way. It is important to note that the third party arbitrator has very limited powers — they can only decide to send the money to the seller or the buyer, and only in a case where the seller or the buyer are in dispute. The arbitrator cannot take the money for themselves or send it to someone other than the buyer or the seller. 1

Careful readers might note that, in order for this to work, the money must be escrowed at the moment of the transaction. Currently, smart contracts cannot take money out of accounts or put liens on future income. Further research should prioritize mechanisms for enforcing non-escrowed payments. This would allow for a wider variety of participants and agreements.

Legal contracts and self-binding commitments

A legal contract, on the other hand, can rely on the state’s “matchless powers of compulsion,” as Kronman puts it. But the power of the state is a limited resource, and, absent a price mechanism, must be rationed. Therefore, the court needs to distinguish between promises that they think are worth the time to enforce, and promises that aren’t. This results in doctrines such as the doctrine of consideration in American law. There is still a significant amount of research required to implement certain credible commitments in the form of smart contracts. However, some smart contracts in their present state can enforce commitments that legal contracts can’t. For instance, here’s an example of a Michelson smart contract, as provided by Milo Davis. It locks up an amount of tez until a specific time, after which it sends the tez to the contract on file.

parameter unit;

storage (pair timestamp (pair tez (contract unit unit)));

return unit;

code { CDR; # Ignore the parameter

DUP; # Duplicate the storage

CAR; # Get the timestamp

NOW; # Push the current timestamp

CMPLT; # Compare to the current time

IF {FAIL} {}; # Fail if it is too soon

DUP; # Duplicate the storage value

# this must be on the bottom of the stack for us to call

transfer tokens

CDR; # Ignore the timestamp, focusing in on the

transfer data

DUP; # Duplicate the transfer information

CAR; # Get the amount of the transfer on top of

the stack

DIP{CDR}; # Put the contract underneath it

UNIT; # Put the contract’s argument type on top of

the stack

TRANSFER_TOKENS; # Make the transfer

PAIR} # Pair up to meet the calling conventionWe might wonder why anyone would use such a contract. Why would you want to prevent yourself from having access to money until a certain time? Because our short term actions are often opposed to our long term goals, and self-binding commitments can help us with problems caused by temporal discounting (Elster, “Ulysses Unbound,” p. 25). 2

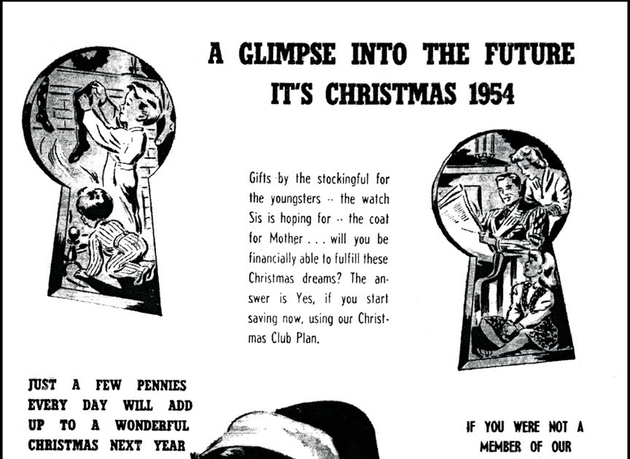

Jon Elster (and later Cass Sunstein and Richard Thaler in their book Nudge) describes such a case. Before the advent of credit cards, parents used Christmas clubs to ensure they would have enough money saved to pay for presents. They would give a portion of each paycheck to the club, and the club wouldn’t give them access to the funds until December.

The law doesn’t recognize one-party contracts of this sort — indeed, the notion doesn’t even make sense in the modern legal framework. But already smart contracts can easily be used for this kind of self-binding commitment, cutting out the third party. Self-binding commitments can be of great use in bargaining (as Nobel prize winning economist Thomas Schelling famously proposed) and are arguably the foundation of constitutionalism (although this remains an active area of research).

Commitments in the Internet Age

With Bitcoin, we’ve seen the start of a revolution in economics, but we’re still waiting for smart contracts to become a reality. Admittedly, smart contracts require significantly more functionality before they can rival legal contracts. However, let us not forget that most people don’t have any access to legal contracts, and disputes can often be prohibitively expensive to litigate. In 2008, a UN commission estimated that a whopping four billion people live without access to the rule of law. Even though smart contracts remain in their infancy, they may meet the needs of the global poor far sooner than traditional institutions will. Smart contracts force us to resolve ambiguities upfront, making legal access scalable and less costly than ex-post adjudication. And as an open source software, smart contracts allow for rapid experimentation in the enforcement of commitments and can improve our institutional capabilities at an unprecedented pace.

Further Reading

Papers and Articles

Milo Davis’ website on Michelson

“Contract Law and the State of Nature” by Anthony T. Kronman

“An Essay on Bargaining” by Thomas Schelling

Books

Contract as Promise by Charles Fried

Ulysses Unbound by Jon Elster

Originally published on the Tezos Medium blog